If people weren’t sure before, Corona hit the message home: video games are a mainstream form of entertainment. Because of the sheer size of the market, game makers can now monetize their audiences in ways that are both similar to conventional media and via novel revenue models. Subscriptions (aka ‘Netflix for Games’) seem to finally take off.

Charging people a recurrent fee offers benefits to both sides of the market. Consumers, on the one hand, get relatively cheap access to a lot of (hopefully curated) content, and content providers, on the other hand, reap the benefits of a recurrent revenue stream in an otherwise hit-driven marketplace.

Platform Economics

Just as we have seen happening in video and music, so, too, in games. Subscription based revenue models for games are popping up and taking off. Microsoft’s Game Pass stands out: it reported 15 million subscribers in September 2020. With the launch of its new console that number grew spectacularly to 25 million subscribers and currently serves as the high watermark for gaming subscriptions among platform holders. By comparison Sony’s PlayStation Now service has only 3.2 million subscribers even as it manages to outsell Microsoft roughly 2-to-1 in consoles.

Long gone are the days when consumer demand was easily described in an annual attach rate (units sold) of 2.4 games per player. Audiences today have a much bigger appetite than that. But the $60 price tag for a box at retail still creates a gamble on whether a game is worth it, or not. Subscription-based services that give access to a broad catalogue of (un)curated titles remove that uncertainty and add value for consumers.

The Supply Side

Quick maths tells us that at an average selling price of $45 per game and an average attach rate, the traditional console player spent $108 a year. In a physical product model, a platform makes about $8 per game, totaling $19 on average annually per player.

Even in a digital model (not accounting for micro-transactions) it would make 30% or about $32. That is better, but not nearly as good as a full year subscription of (12 * $10) = $120 on the low end. Yes, there is a cost involved with filling up the catalogue, but it reduces demand uncertainty and solves the persistent problem of used game sales.

But that’s not all. In contemporary platform economics it is imperative to have some type of subsidized offering that will draw lots of users to their ecosystem and then cross-sell a range of different products and services. By subsidizing game subscriptions, Microsoft is trying to build a global addressable audience for its software services. It knows all too well from previous misfires with Nokia and Mixer that building a successful platform means getting there early.

Content Creators

The economics of recurrent payments has not gone unnoticed by content providers. One benefit is that it removes the need of constantly having to convince players to spend just a bit more money on something. That’s not a huge cost necessarily, but it can negatively impact the length of a player’s life-cycle and cheapen the experience. Fortnite offers its own subscription: Fortnite Crew. In the shadow of its ongoing struggle with Apple over App Store fees, Epic Games launched a subscription package that is slightly more expensive than its existing Battle Pass but also offers more.

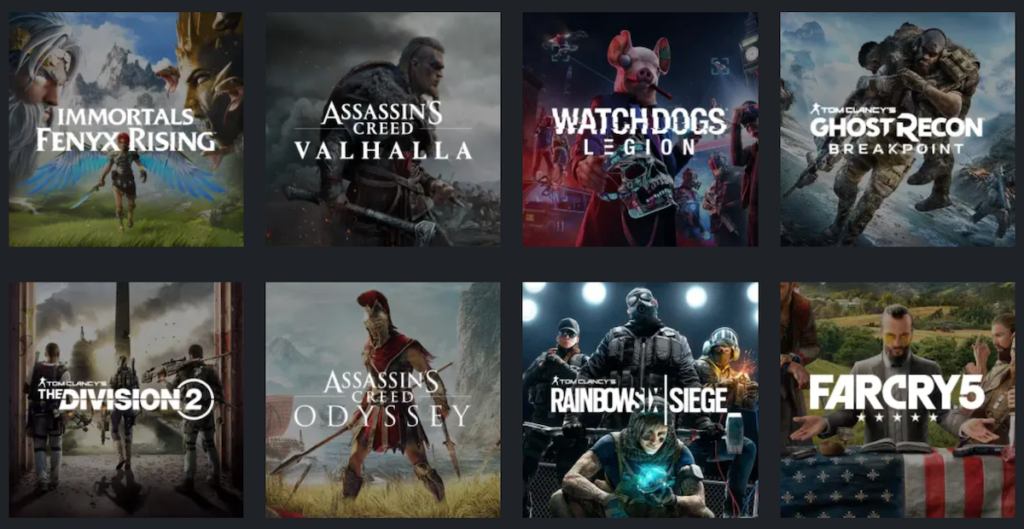

Others sell access to a selection of their catalogue. After Ubisoft’s horrid first attempt at establishing a social layer under the moniker UPlay (which sucked), the French publisher now offers Ubisoft Plus. It certainly remains a work in progress. But there is something quite magical about picking up in Valhalla on Amazon Luna from where I left off on my console.

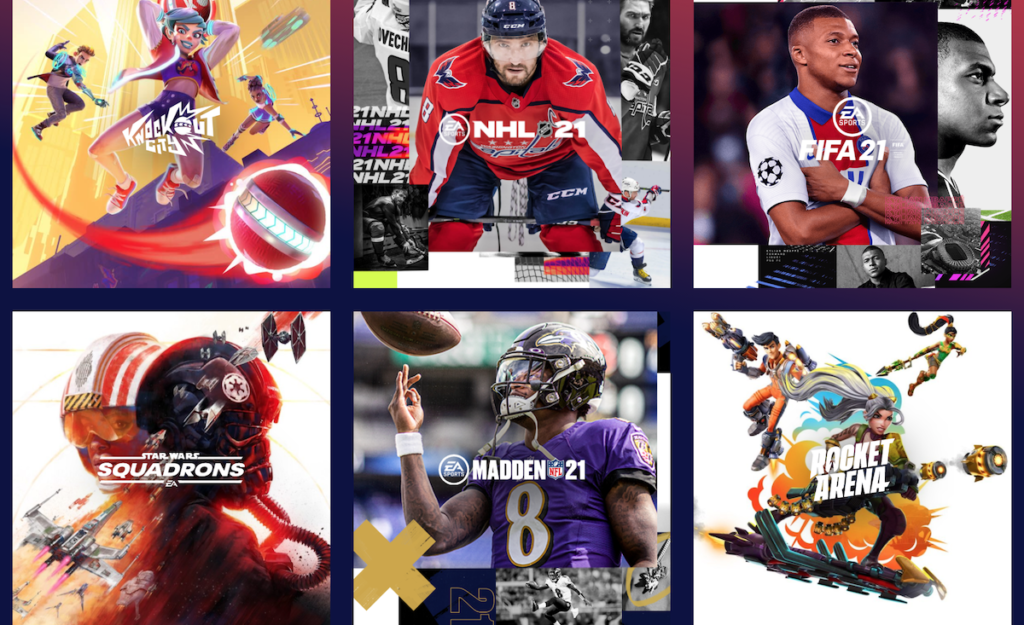

EA Play similarly offers a buffet of older titles which bundles nicely with the release of new hardware, of course, but currently seems largely focused on generating accretive revenue rather than shaping it as a spearhead in its digital strategy. And in fairness, you also have to ask yourself whether that ultra-loyal audience that buys the new version of NFL Madden/FIFA every year shouldn’t be regarded as subscribers anyway.

Fear for Subscriptions

One explanation is that legacy publishers are only in the early stages of adapting this revenue model. A decade ago their inherent aversion to risk meant that these firms were equally slow in adapting free-to-play. So it is nothing new. Their fear around subscriptions is that they’ll eventually be forced into providing access to their entire catalogue for a single price as cross-platform play becomes more prevalent and hardware more fragmented.

Recurrent revenue offers legacy publishers a more predictable cash flow and improves player loyalty. That is a welcome change from the traditional hit-driven, win-or-die dynamic in interactive entertainment. But more important than making the CFO’s job easier, subscriptions also yield a higher valuation among investors for publicly traded firms.

Service-based companies trade at multiples in the range of 10-20 times revenue, compared to the 2-5x revenue for product-based firms. That is a massive difference and reduces the cost of capital. On the short term that’s a nice to have; on the long term access to cheap capital is a must because publishers will be competing over IP and talent. And neither of those are getting cheaper, as Take-Two found out last year when EA elbowed it out of the way to buy Codemasters.

Game publishers as TV networks

Subscriptions are only as lucrative as you’re willing to make them. Stay stuck in a model that is governed by a product-based release schedule and you’ll barely cover your costs. What we’ve learned from Netflix, HBO, and most recently from Disney’s loud-as-hell tripling of its subscriber base forecast for Disney Plus is that you must commit.

That means that both game publishers and platforms must either offer up their premium first-party content, or accept that they’re not serious about subscriptions. With seven million subscribers, EA Play holds the promise of something great, but it is still early. Once Sony resolves the supply issues for its new device, merely suggesting to add The Last of Us Part 2 to its PS Now service will positively impact the size of its user base, revenue forecast, and share price in one swoop.

Game publishers, especially the ones that control well-known intellectual property, are slowly becoming TV networks that each target a specific audience. EA attracts the sports fans and a declining number of Star Wars fans. Take-Two offers edgier content that others don’t want to touch. And Ubisoft focuses on volume. They’ll each try to monetize like an HBO and, just maybe, vertically integrate like Disney.

Content buffet

The major challenge among game makers when it comes to subscriptions is the anxiety to disappear in a content buffet. Like music, the value of a game originates in people playing it. In that category we currently see a music rights gold rush as companies are eagerly buying up well-known artists’ catalogs to sell to streaming platforms.

Because playing games is different from playing music, it will be hard to differentiate for medium-sized game companies and middle-of-the-road content. Their challenge is to command enough player attention to earn a high fee from platforms, whose economics dictate that they offer a lot of content for a little and then make a profit in a wholly separate category (e.g., Amazon). That makes content a loss-leader to drive user adoption of a specific proprietary ecosystem rather than the blades that justify the subsidization of the razor.

Wall Street’s obsession

More generally, the proliferation of subscriptions and their emergence as a dominant revenue stream in gaming is a function of the myriad of benefits it offers to gaming companies. Players, platforms, and publishers alike stand to gain from agreeing to a monthly fee. The cost of doing so is also relatively low compared to conventional product-based releases. But above all it is Wall Street’s obsession with recurrent revenue that is going to drive a frenzy in subscriptions: valuing companies that generate income on a monthly basis roughly 10x higher means it is worth it to implement this revenue strategy just to capture that additional value.

As a result content creators will be designing games in a different economic context. Games that are sold to a platform or added to a bundle are different from the ones that need to convince a player to keep putting a quarter in the machine. Games will become mere line items in a cost plus pricing scheme rather than fetching a premium price. So, too, has filmmaking become a different sport with Netflix and Amazon pouring millions into the category. Why ask Netflix for $2 million to make your movie, when you can ask for $20 million?

Taking the volatility out of the equation and subsidizing a growing inventory of content is a strong strategy as the industry’s platform economics start to change. I expect a lot of firms to subscribe to that.