A few times a year, the release of a film based on a video game franchise offers a moment to check in on how the two industries relate.

Historically, their dynamic hasn’t been great. Video game adaptations were a sure way to lose a lot of money. Often no more than a sideshow, brand managers would sell off the movie rights to producers that barely played games or understood the lore for even the biggest franchises.

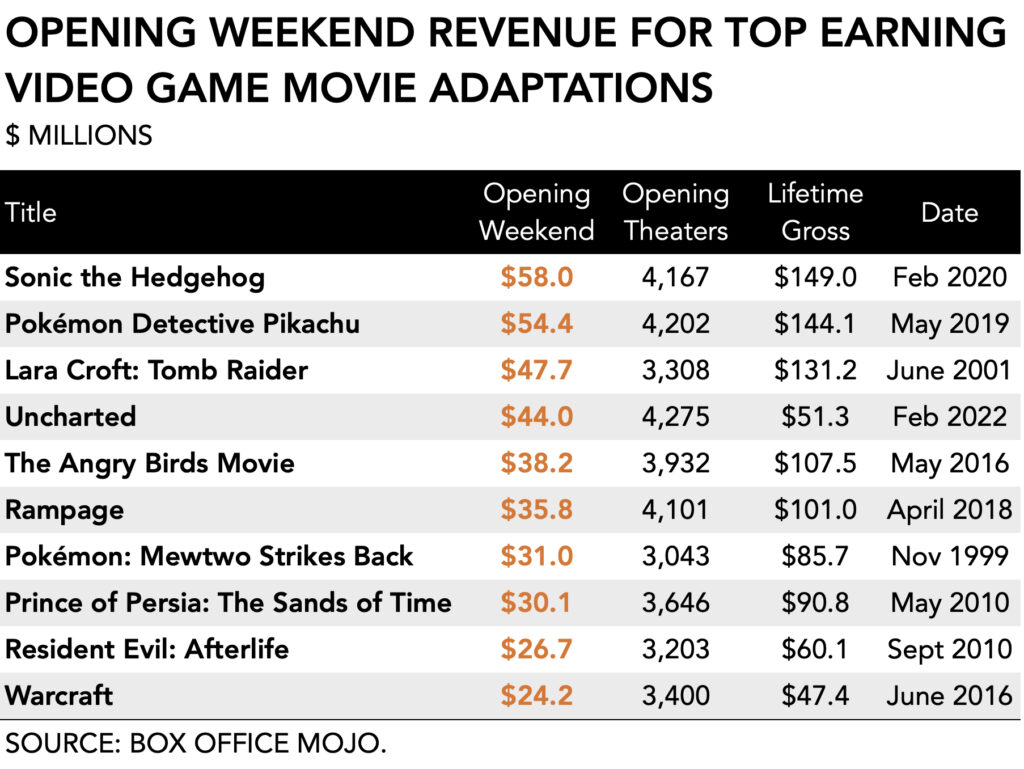

According to most filmmakers, video games were simply a lower rung on the cultural ladder and undeserving of any real artistic attention. And, fatally, adaptations proved a terrible financial venture. In the decade between 2000 and 2010, the average production budget for a video game adaptation was $52 million. But the average profitability of $40 million meant that on average films in this category lost -23 percent. Exceptions characterize this period. Tomb Raider (2001) remains one of the top-grossing films but pretty much all other game-related movies from that time sucked.

Since then things have changed. The rapid popularization of interactive entertainment resulted in an increase in demand. Audiences don’t just want to play a game, they want to inhabit it. Financial outcomes shifted accordingly. Since 2010, production budgets increased +46% to an average of $77 million and profitability jumped to +95%, for an average of $150 million per film.

Hollywood and gaming

Certainly, there exists an enormous spread between different productions and their box office successes. But given that the average number of opening theaters for films in this category has increased from sub-2,000 in the late 1990s to well over 3,000 today tells you that Hollywood is leaning into gaming.

More so, video streaming services have discovered fertile ground in gaming. Netflix has been spending a lot of time and attention on producing binge-worthy series based on The Witcher, Castlevania, League of Legends, and others. Sure enough, Hollywood considers video game IP now good enough to serve its financial needs. But isn’t the games industry selling itself short?

I think it is. In fact, I’ve argued previously that the games industry continues to be wildly insecure about its own cultural significance. Releasing a film or TV series somehow seems to mean it is relevant. It doesn’t. But so many of the current decision-makers in the games business are deeply convinced that gaming is merely a creative stepping stone into more established entertainment industries.

Cherry picking

In fairness, the game Uncharted borrowed generously from Hollywood. Its main character, the narrative arc, the Indiana Jones-style adventuring, and the treasure hunting are all obvious movie tropes. In fact, the whole franchise is an interactive, albeit railed, movie. Similarly, something like The Last of Us 2 is deeply rooted in the apocalypse survival genre that proved so popular on TV even if you’d be hard-pressed to find an equivalent gut-wrenching experience on your idiot box. More broadly, much of the North American games industry has traditionally borrowed from Hollywood’s playbook. The underlying economics, development, financing, and marketing resemble those of large blockbuster productions.

But for me, it falls apart in those moments where the games industry offers up the best of itself for something of lesser value. A single silver screen production offers a highly reduced extract from an interactive experience that can take up to 80 hours to complete. Rather than paying homage and making a humble contribution, film and TV makers are more interested in cherry-picking key narrative elements. In the announcement for the Halo TV series, the focus immediately went to revealing Master Chief’s face. After twenty years of mystery and mythology, the literal first televised show wanted a scoop and set the tone. And Master Chief’s voice will be new to all of us, too.

The usual boomer-cynicism

Finally, beyond the imbalance of the current relationship, novel forms of entertainment will emerge from the exchange between video games and film. The current obsession with the metaverse is mostly going to manifest itself from their dialectic. Already did we suffer through Ready Player One and its wild ideas about what gamers are like. So, too, did Black Mirror present us with an image of players that can only be described as sociopathic. And even a kids movie based on an arcade game like Wreck-it Ralph 2 pulled no punches presenting us with the usual boomer-cynicism on what online life looks like.

Meanwhile, the Avengers and Master Chief come together in Fortnite to do a jig and enjoy themselves. The literal playfulness of online environments allows for a broader range of creative expression and expertise. It suggests that franchises that originate in gaming will become more popular in the years to come because they don’t require the type of strict control that characterizes Hollywood. The same iron-fisted solipsism that has served movie makers so well may prove less useful in a metaverse filled with messy interpretations of new and old franchises.

The games industry shouldn’t sell itself short now that filmmakers take a liking to its IP at the dawn of a new era in entertainment in which interactivity leads and passive consumption follows.