Top image: Simulacra by Claud Z

The pandemic has taught us that a reality in which we blend our physical and digital lives isn’t quite as far away as we thought it would be. Even the most ardent opposers of gaming–teachers, employers, parents, and politicians–all found their way online to re-connect with pupils, employees, kids, and voters.

The metaverse, and the myriad of underlying creative and commercial activity from which it springs, proposes a new epistemic space. We will be able to do things we haven’t before such as attend live concerts with millions of others at once and interact and exchange in ways that are, ostensibly, better.

Such a thing isn’t new, of course. The television was initially positioned as a delivery device that would facilitate the distribution of education by the best and brightest to those who had been denied access. Similarly, the information superhighway was going to democratize access to libraries and knowledge and make us all better citizens. I think it’s fair to say that both have yet to deliver on much of their promise.

Epicentre of civic life

Instead, what TV and the internet have in common is that they managed to become the epicenter of civic life. You cannot get elected unless you spend lots of money on a TV campaign. Live events are a necessary anchor of day-to-day activity. Watching a season finale together or a World Cup match is a riveting experience because we know others are watching it, too. To have a sense of social interaction during the various lockdowns, people took to online games and digital social spaces to interact.

In academic terms, logging in to see what’s going on offers confirmation that there is indeed a sense of continuity in the events and affairs of society at large. Social media channels like Twitter are excellent at this. And games and virtual worlds are expected to add a third dimension.

Metaverse pioneers

Admittedly, the metaverse isn’t here yet. I mean, at all. But to get a sense of what it might look like we can take stock of the different firms preparing themselves to lead the revolution.

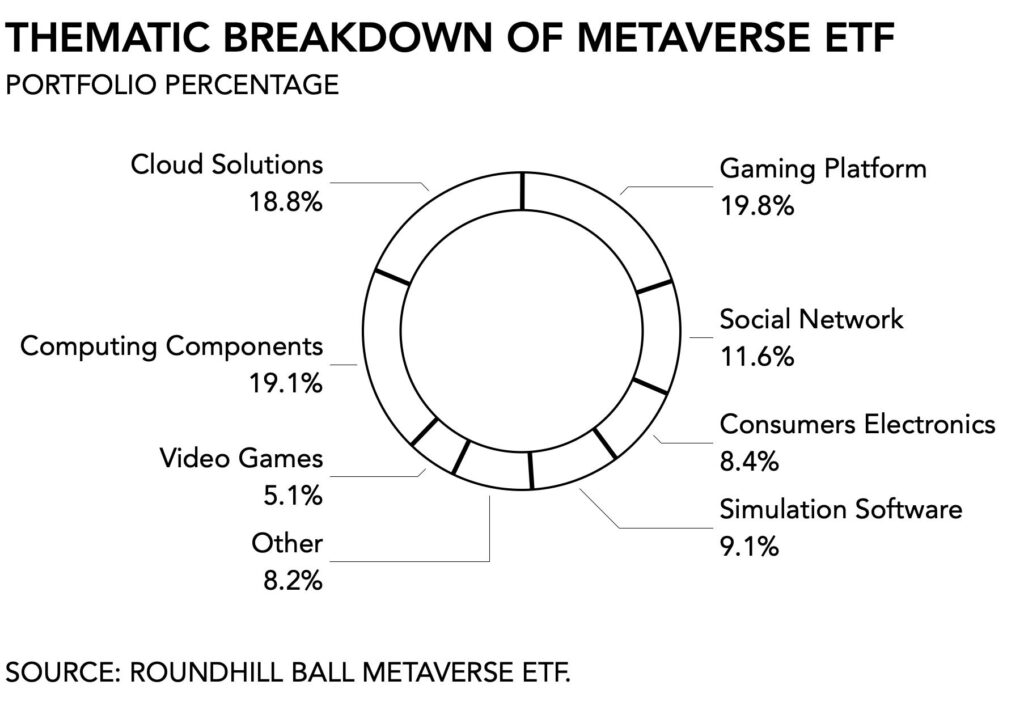

An easy place to start compiling a shortlist of metaverse pioneers is the Roundhill Ball Metaverse ETF (RBME). Matt Ball believes it contains at least 41 companies that “are actively involved in the Metaverse.” (For a full list go here.) So far RBME has reported having $500 million in assets under management since its launch over the summer. These firms are organized by key themes as indicated below.

Two immediate problems emerge. First, there are way too many incumbents involved. Sure enough, I can see why Meta is keen on being part of this future. After Zuckerberg missed mobile and had to haul ass to catch up, he’s been spending generously (see: Oculus) just to stay ahead of the competition. More terrifying than a competitive application is missing an entire technological shift. But disruption doesn’t take prisoners nor does it play favorites.

Reluctant game makers

Similarly, legacy game makers are unlikely to make a big splash here. If Activision Blizzard even succeeds in neutralizing the current slow-motion implosion it triggered on account of its executive dysfunction, then it is still unclear if it can meaningfully contribute. When it comes to novel technology it has historically not shown itself a leader and shows a preference for purchasing successful entities at a premium (e.g., Blizzard, King Digital) rather than nurturing innovation from the ground up.

Competitor Take-Two is enamored by web3 technology like blockchain and non-fungible tokens, but seems otherwise skeptical of the metaverse, arguing that it already exists. “I would argue we’re probably the biggest metaverse company on Earth if you look in terms of revenue and profits because we’re in [‘Grand Theft Auto Online’], which really I think defines the metaverse today, ‘Red Dead Online’ and ‘NBA 2K’s’ online version.”

Happy avatar

Microsoft has presented us with a rather terrifying visualization of floating torsos that are now going to be replacing corporate meetings. During my preciously short work experience at a large firm, I watched under-staffed and over-worked HR and legal departments suffer through byzantine software applications. The last thing they need is having to create some happy avatar.

And, certainly, NVIDIA’s stock has skyrocketed. But the firm suffers from regulatory pressure on account of its acquisition of AMD. And the current supply chain issues are, by some accounts, just a taste of what’s to come.

Investors

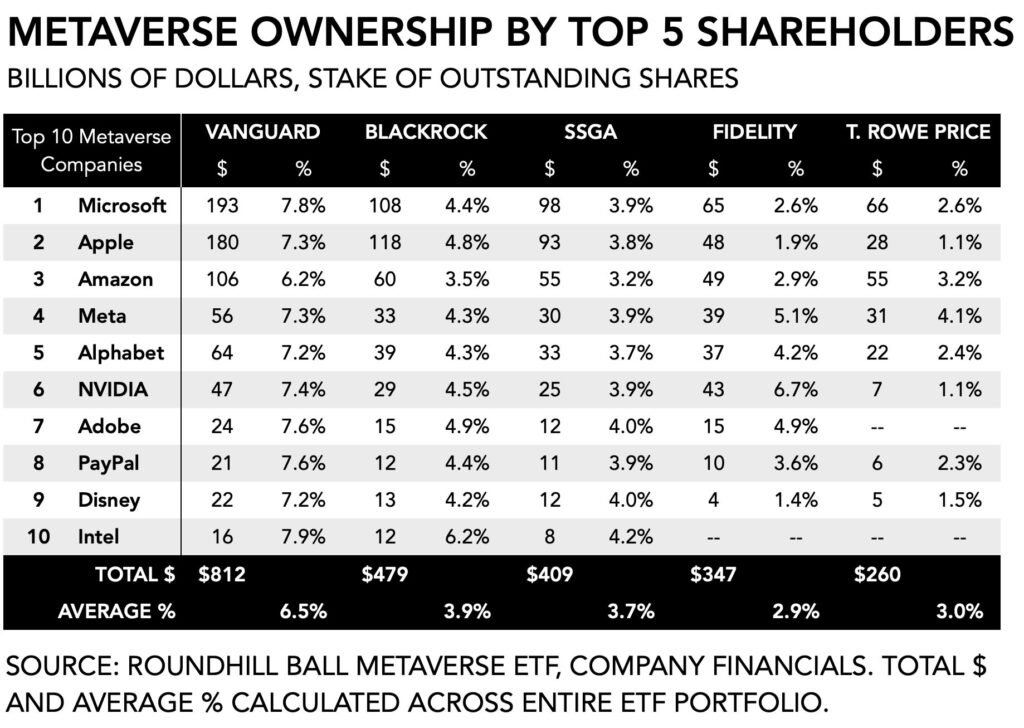

The best thing we can say for these companies is that if we go up one floor and look at the largest shareholders, there is perhaps some room for optimism. Major investors like the Vanguard Group, BlackRock, and others do hold substantial shares in the RBME consortium. This is consistent with maintaining a diversified portfolio.

The Vanguard Group holds shares in 36 of the 41 firms in the RBME portfolio. BlackRock has 34, Fidelity 29, SSgA 28, and T. Rowe Price 20. That tells us the current ‘ownership’ of the metaverse by large investors is roughly in line with their historical financial positions in mass media, telecom, and IT verticals. They are, however, also the usual suspects and foreshadow more of the same.

There’s more here, of course, but for brevity’s sake, it is not entirely clear just yet how these firms are going to lead the transition. We grew up with the knowledge that the revolution would not be televised. With this crew, it is also unlikely to manifest virtually.

Lack of diversity

Second, the abject absence of diversity is alarming. One of the major hindrances in tech and gaming has been the absolute ubiquity of men. The masters of the metaverse are, so far, almost exclusively sourced from a single gender. Based on the RBME group, there is exactly one woman in a leadership position: Lisa Su at Advanced Micro Devices. The rest: all dudes.

Arguably the RBME list is limited. But even if we widen the total pool of firms that are building the metaverse and use Jon Radoff’s more extensive list that includes also privately-held firms like Epic Games, we count only seven women out of a total of 142 companies.

It’s like Vegas

Personally, I’m only mildly interested in a male-governed metaverse. I’ve been to Vegas. It’s so-so. The whole point of such an evolution, or even revolution, in media technology would be the deliberate and purposeful inclusion of a broader array of voices. The question as to who owns the metaverse remains unanswered. That’s because we’re only at the beginning of this novelty and still have a chance to build something new.

Imagine a world in which organizations don’t just start cleaning up their work culture once they get caught, or suddenly find the need and budget to hire a diversity manager after years of toxic behavior. Similarly, the meta-marketplace of ideas can only really exist if its architects manage to bring a broad set of experiences to its design.

This is not that.