German indie game studio DigiTales Interactive created two sci-fi detective adventures for PC and consoles: Lacuna (2021) and Between Horizons (2024). While the first game performed well, selling over 300,000 copies across platforms, the second has fallen far short of those numbers and has yet to break even. That’s enough for Julian Colbus, CEO of DigiTales Interactive, to wonder: “Why is that? Are we just a one-hit wonder? Did we peak with our first release, doomed to forever chase that high?”

In his brutally honest post-mortem, Colbus examines what happened during the four years of Between Horizons’ development and, in his own words, aims to: “Caution you about all the mistakes I’ve graciously made so you don’t have to.

By: Julian Colbus

Part 1: Suffering from success

I’ve often heard people say that the beginning is the most difficult part. When you have no idea what you’re doing yet, and the task ahead is a vast, uncharted mountain range that disappears into the clouds – that’s what your first big game project feels like. The majority of people don’t see it through, and even most of those who do never make a second game. This comes as no surprise as statistically, your game will crash and burn commercially.

Now, picture this: Your very first game gets signed by a publisher. You manage to secure a 6-figure amount in funding. You finish production in time, and it’s a success beyond any reasonable expectation. It even goes on to sell 300.000+ copies across platforms, win awards, and receive accolades from players and journalists across the globe. You’ve made it, right? Things only get better from here, right?

This happened to us with Lacuna. Then came our second game Between Horizons. All told, its production was far from a disaster compared to many industry horror stories. We did manage to finish it without severe burnout, and it turned out pretty good. However, despite having learned so much from our first game, we ended up finding a plethora of new mistakes to make. To an extent, I now believe that being in a comfortable position for a while, having secured funding for a few years worth of development, made us a little complacent. Not in the sense that we were ever lazy, but that we took too much time for irrelevant things while our budget was slowly melting away. To expand on the mountain climbing metaphor, we were obsessed with security on our first ascent, only to forget clipping in our carabiners on the second.

Lukewarm reception

Ultimately, Between Horizons took more time and money to make than I had estimated, and I’m about to lay out extensively why I think that was – but even if it hadn’t, its commercial prospects were never looking great. Public reception was lukewarm from the beginning. Even though our publisher submitted the game to many festivals, awards, store events etc., it wasn’t wooing people the way we had hoped. This trend continued after it came out: The game did launch with more Steam wishlists than Lacuna had due to a longer pre-release period, but conversions were slow to come in. It doesn’t take an expert to deduce, just based on publicly available data, that Between Horizons likely hasn’t made its money back yet. As of September 2025, it sits at just over 400 Steam reviews, which does not measure up to the (relatively modest) production budget of a game this size.

That being said, if it had been our first release, I would feel differently about it. Tens of thousands of people have played Between Horizons, and 91% of Steam reviews are positive – that’s still something to be proud of, and it puts the game above the vast majority of releases on the platform. However, a year and a half after its release, it is lagging behind Lacuna by a wide margin. Why is that? Are we just a one-hit wonder? Did we peak at our first release, doomed to forever chase that high?

Fortunately, I don’t think that’s the case. Let’s dive into the much more complicated truth.

Part 2: Growth for growth’s sake

Some of the takeaways in parts 2 and especially 3 are very subjective and will only apply to certain situations and personalities. If you’re an allrounder like myself working alone or in a small team, I might be able to caution you about some potentially costly mistakes. If you aren’t, there are still many general considerations in there for you, such as finding the right game to make next.

Play it safe

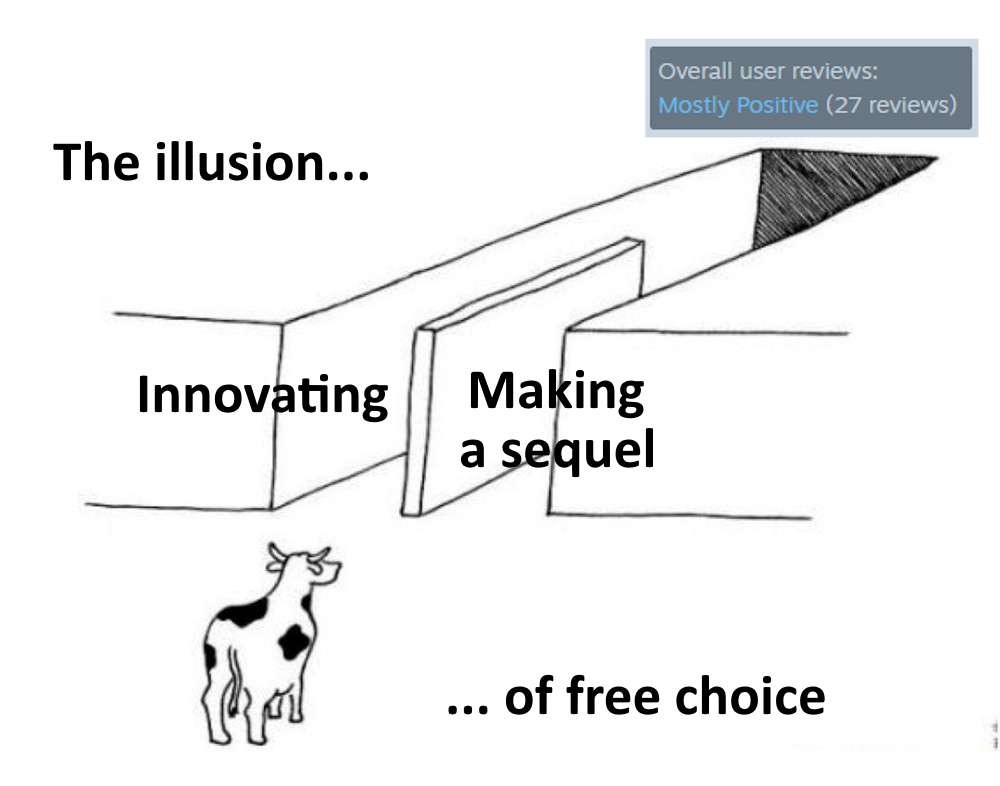

Success is when the numbers go up, right? If your first game made its money back and then some, capitalist logic dictates that it’s time to expand. The next one will be more ambitious in every way, requiring a bigger team and budget. With the bigger investment comes a bigger game, comes a bigger audience, comes a bigger return on investment. Money printer go brrrr!

Not at all. Do not fall for this trap.

Don’t fix it if it ain’t broken. Do not grow the team, do not expand the scope of your project, do not increase the budget, unless you have a banger of an idea that absolutely requires you to. If your first game was successful, your learning should be “keep going”, and not “change it up”. Even though we somewhat stayed the course by making another narrative sci-fi detective game, and the changes to the formula were well thought-out based on decent game design ideas, the required expansion of the budget killed any chance of breaking even in an acceptable timeframe. Know your niche, and be realistic about the return of investment you can expect.

Success comes in many different forms. If you run a 3- or 4-person studio that can comfortably exist for decades without a major hit, I would call that an incredible feat. It would make me very happy, and in hindsight I don’t know why I didn’t aim for that in the first place. In my mind, success meant we had to grow, which it simply does not.

Don’t play it too safe

All that being said, I have another piece of advice. Do not make a sequel either. This is admittedly not something we learned first-hand, as we decided against it early-on. I want to explain the reasoning behind this, since you might have been yelling “IF YOUR FIRST GAME WAS SO COOL, WHY DIDN’T YOU MORONS MAKE A SEQUEL THEN” at the screen for a while now.

At least looking at anecdotal evidence, the sequels created by our fellow indies always seem to perform worse, often far worse, than the first game of the series. I doubt that this is because sequels are consistently just worse games. Imagine this: You’re browsing Steam and see that Awesome Game 2: Return Of The Awesome just released. It’s 10% off for the first week, but the first Awesome Game is 75% off in the same period for a nice little synergy effect. You click that one because you haven’t played it either yet, and maybe it makes more sense to start the series in the beginning. Perhaps you decide to buy Awesome Game 1, or perhaps you realize that it’s been sitting in your library for two years already, completely untouched. You put Awesome Game 2 on your wishlist and decide to wait for it to be more steeply discounted. After all, you haven’t even gotten around to Awesome Game 1 yet. A year later, you get a notification that Awesome Game 2 is now 50% off. You still haven’t touched Awesome Game 1, or maybe you have, but you never finished it even though you liked it alright. As soon as you finish it, you will surely buy Awesome Game 2… (None of that will happen.)

That’s just a story, but maybe it sounds relatable to my fellow adult gamers out there. If someone has data specifically on sequels that backs up or refutes my thinking here, please hit me up! I’m happy to amend this paragraph.

Here’s how to play it, maybe

Looking back, I believe we should have stuck closer to Lacuna with our second title. After all, we had only just gotten the hang of it. Changing the art style (adding a 3rd dimension no less), and making the gameplay formula much more open-world were unnecessarily drastic changes that threw us into deep ends we didn’t even need to be in. Iterating more slowly and maybe even narrowing the scope, really getting to the core of what makes the detective genre fun, would likely have been the better approach. (I can neither confirm nor deny that this is what we’re doing with our third game.)

That being said, many studios completely change up the genre from one game to another. There can be good reasons for this, but they need to be reality-checked. The same goes for upping the scope and budget, which I cautioned earlier to only do if your banger idea justifies it. I urge you to test your new idea in every way possible, as early as possible, before you start throwing money at it. Do not start by hiring new people to realize the idea; develop an MVP with your tiny team and show it to your intended audience. There is no other way to find out if it is indeed a banger and worth expanding or switching genres for.

See what sticks

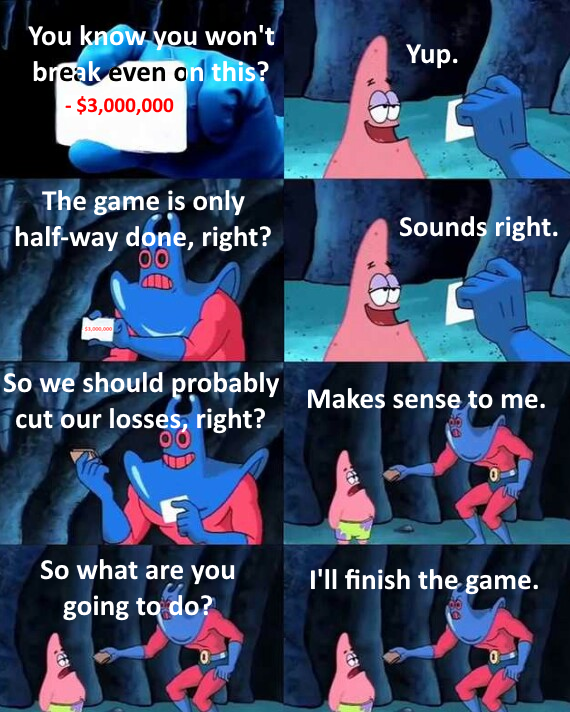

In fact, I’ll go one step further: The new meta might just be to throw a lot of concepts at the wall – the wall being Steam – and see what sticks. Put together a concept for a small game with a clear focus, set up a store page, and create some buzz with as little time investment as possible to gauge interest. Set up kill gates (obtain x wishlists in y months) and consistently scrap projects that don’t make it across. If something has legs, make an actual game off the bullshots. I’m personally (at this point in time) too idealistic and too passionate about certain ideas, but this seems like a commercially sound strategy compared to what most of us indies do – flying blind for years in the hopes that someone will care once we get there. Maybe if more of us tested ideas early this way, the majority of indie games wouldn’t be years-long sunken cost fallacies.

Part 3: Focus on your strengths

I’ve made it clear that wasting money on tasks, services, features, and ultimately time that we did not actually need was a major mistake on my part. However, there is another hidden cost to it, which might be the most detrimental to both the project’s final quality and the pace of its production: While I was a major creative force on Lacuna from beginning to end, directly working on literally all aspects of the game, I spent more than half my time on Between Horizons with management. This is not to say management is terrible or unnecessary, but it has two severe downsides.

Don’t hand off your baby

First, I effectively left much more of the creative work to others. Although many people made fantastic contributions to Lacuna, it was in large part my brainchild, and people liked the creative work that I had personally put into it. My co-founder and I wrote the entire story and in-game texts, co-designed all of the cases, put together all the levels, and implemented the entire story logic. On top of that, I composed the entire soundtrack safe for two guest tracks. With Between Horizons meanwhile, I handed off much more of the creative work to others.

It may be obvious to most readers, but it bears repeating that productivity does not scale linearly with the amount of people. If one person can make a game in a year, then twelve people can make that same game in a month, right? Every employee adds an overhead of communication and bureaucracy. Think hard before putting all the time and energy of (presumably) your most productive worker – yourself – into maintaining this structure, especially when you have already proven to do good work in other areas that would receive less of your attention.

My decision to voluntarily maneuver myself into more of a management role is another one I do not understand in hindsight, and not just from an efficiency standpoint. Spreadsheets, sprints, and effort points aren’t not fun, but they’re certainly not why I got into game development – the creative part is.

Don’t surrender control

Second, I lost all control over certain aspects such as the code base and the 3D art workflow, neither of which I had the time to learn much about. This didn’t just make me feel uneasy, it had severe ripple effects that frequently slowed down the project. Whenever there was a technical issue in the project preventing me from doing my work – which happened a lot –, I had to ask a programmer for help. Sometimes this would mean calling them over, interrupting their current work and ultimately losing a lot of time to task-switching. To prevent this, I’d often opt for creating elaborate tickets instead, with all the steps to reproduce the issue and some captured footage to go along with it. Waiting until someone got around to the ticket would in turn often take multiple hours or sometimes even days. As a self-employed person, I have no qualms working into the night, on weekends, and holidays, but I’ve never expected this from anyone else. I would oftentimes open up Unity on a Saturday, a fresh cup of coffee in hand, not having to worry about emails or other nonsense interrupting my work – only to quickly realize that the project was not in a state for me to do any of it.

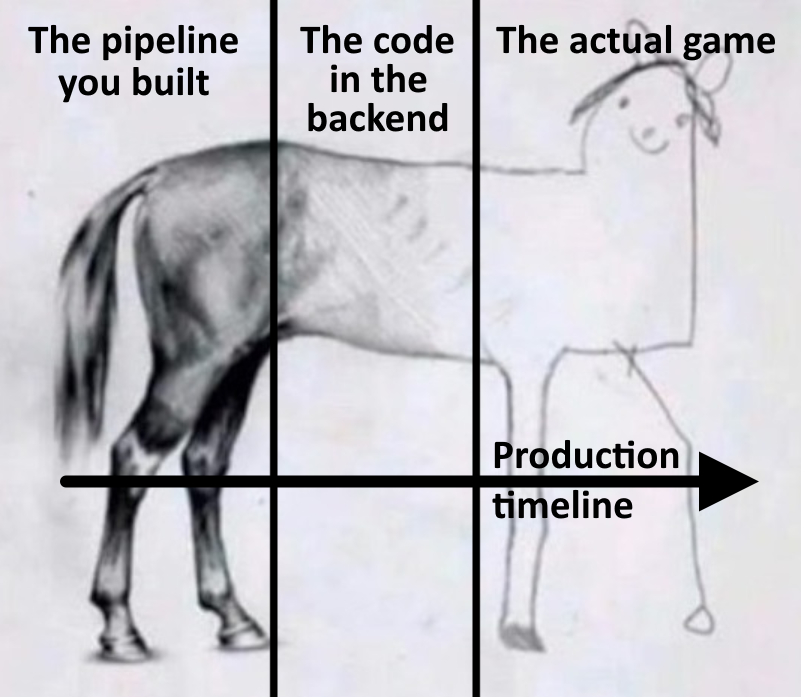

With Lacuna, even though I wasn’t the main coder, I was always knowledgeable enough to look into such issues myself. Some stretches of the Between Horizons production would have progressed much faster if I hadn’t completely surrendered control of the code base. Making it worse is the fact that now, after the programmers in charge left the company, it’s incredibly difficult to address bugs or make other improvements to the game. This is especially true for the Xbox and PS5 ports, neither of which the remaining team had much involvement with.

Don’t build what you don’t need

I know what some of you are thinking: “You don’t have to do it all yourself. Just give better directions. And for the love of god, restrict people from pushing to the production branch on a Friday afternoon when there is no system for pull requests or automated tests.” We did spend a lot of time establishing, documenting, and enforcing rules and systems for our work and communication at the pre-production stage. We threw half of them out the window as the overhead was just not worth it for a team our size. I get that I can’t have it both ways: Playing it fast and loose so the game actually gets done, and then complaining that it’s not always in a playable state. This is a tough line to walk, and reasonable people will often disagree in this technical area. When is a shortcut worth taking? How modular and extendable will this bit of code really need to be later-on? At what point is it no longer a time-saver to develop this tool further? And so forth.

It just so happened that I often listened to people who were more well-versed in programming than me. In hindsight, I should have stood my ground because I was the one with knowledge of the budget and timeline, and with a decade of experience under my belt, programming degree or not. It was my responsibility to balance the goals of my team members and decide when something was good enough. After all, to a hammer, everything looks like a nail. An artist will try to make the game as pretty as can be, a game designer will want to make it the most fun, and a programmer will want it to have the best code base. And while all of them need to manage their expectations, I feel the need to point out that great art direction and game design have won countless awards, while clean code has not. If your game can be held together by some duct tape and a prayer, it arguably should be.

Of course, our games are simple; they won’t grow out of control, and we won’t need to accommodate complex, possibly yet unknown features down the line. A quick and dirty approach often would have worked, down to the very foundation of the game. It did in Lacuna, which wasn’t much simpler than Between Horizons, and – here’s the kicker – broke a lot less frequently throughout the production phase. When it did, fixes were quick and simple.

My experience at times has been that somebody given a task will often take exactly however long you give them for it. The extra time is spent on making it nicer, cleaner, or more elaborate, not necessarily better in way that’s worth it or sometimes even tangible. This is especially true for programming tasks; a system being more elaborate does not always make it safer, more future-proof or less prone to breaking – it does, however, often make it harder to understand, maintain, and fix later, especially by someone who didn’t write it. I should have followed my gut more often and made executive decisions sooner when things were taking too long, or when we were working on something irrelevant to the player experience (which was usually my own, incorrect call to begin with).

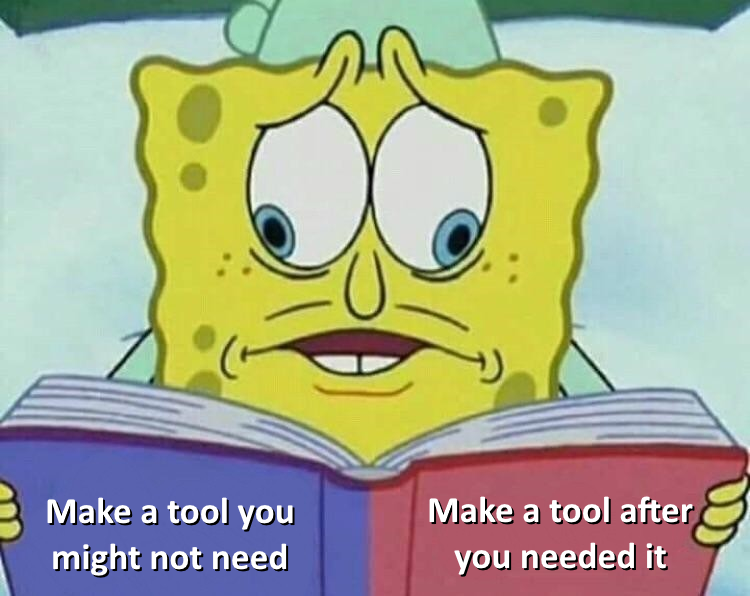

To expand on this last point: Never, ever make a feature or tool because you think you might need it later. Did you know, for example, that NPCs in Between Horizons can not only call, but use elevators? And that they can enter them together, stepping out of each other’s way, and exit them at different stops, all integrated with our pathfinding system? If you’ve played the game, you may be correctly remembering right now that NOT A SINGLE NPC EVER EVEN USES AN ELEVATOR. This was another moronic waste of resources on my part that I stopped way too late.

Part 4: Everything else that went wrong

So far, I’ve been focussing on strategic failures that hindered the production process. While they did make it harder to break even by increasing the project’s development time and budget, they didn’t necessarily set it up for commercial failure. Some competitors in the detective genre, including our own first game, have proven the niche to be way bigger than the audience Between Horizons is reaching. So why aren’t they buying it?

The product

Regardless of your personal opinion on some mainstream titles, we can all agree that a terrible game will never sell well. But a terrible game does not score 91% on Steam and 83 on Metacritic. A masterpiece would’ve certainly sold better, but Between Horizons’ main issue isn’t quality – it’s marketability. Unlike the marketing itself, which fell on our publisher, this aspect was in our hands alone, and we failed big time in my opinion.

When you’re coming up with a game idea and subsequently go about its realization, you should keep marketability in mind at all times. By this I do not mean “include a completely unnecessary cute character so you can sell plushies to children later”. I mean “create a product that will be able to immediately communicate the experience players will get”. Our first title Lacuna had an on-the-nose noir setting with a brooding, smoking, trenchcoat-wearing main character that we plastered all over the game’s key artworks and trailers. Mood, setting, and protagonist being recognizably taken from detective stories created an expectation that there might be detective gameplay. We did mess up the title – because what does “Lacuna” even mean? –, so we added the subtitle “A Sci-Fi Noir Adventure”. Games that did a way better job on this include “Case Of The Golden Idol” (there’s a case, so you’re a detective) and, maybe the best example, “Duck Detective” (you’re a duck who is a detective, duh).

Awful title

I used to think that all those long isekai manga titles were silly, now I think they’re brilliant. It’s true that nobody reads past the title anymore, so you might as well put the whole premise in it. Maybe it’s just a matter of time until games like “Help! My girlfriend turned into a fridge, and now we have to battle through a grocery store dungeon together” start blazing a trail on storefronts across all platforms. Half-jokes aside, “Between Horizons” is a similarly awful title to our first. At least it vaguely suggests sci-fi – but then we made the crucial mistake of commissioning a redundant key artwork that does the same. Here’s how I imagine people saw the artwork for the first time:

Nothing about the title, the artwork, the art style, even the setting hints at the most important thing: the gameplay. This is why we decided to change the key artwork to something more mysterious and add the subtitle “A Sci-Fi Detective Adventure” over a year after release. We bundled it with a mid-sized update to the game addressing countless small issues that players had reported, and it was very well-received by the community. Unfortunately, it’s incredibly hard to catch a second wind once the Steam algorithm has made up its mind about your game. At least it’s not completely dead in the water, steadily gaining about 5 reviews every week. The impact of the rebrand is impossible for me to determine, but I like to think it helps prop up the long tail at least a little.

The marketing

So we agree that a terrible game can’t sell like gangbusters, but the more interesting question is: Can an amazing game sell terribly? I would certainly sleep better at night knowing that we made a perfect product, and our publisher simply failed to market it.

Nothing works anymore

While I do think the marketing for our game was stingy and lackluster, this seems to be the norm nowadays across publishers, studios, and PR agencies. Even the better efforts are constantly failing, especially lately. I recently had a chat with a friend whose latest indie production failed to gain traction and sold miserably on release. This is despite the game looking polished as hell, being a few million euros heavy, and the studio having thrown thousands of euros per month (!) at an established PR agency. Their coveted advice included industry secrets such as “maybe make another Instagram post” or “try sending out a newsletter”. When nothing seemed to work and wishlists remained far south of 10.000, my friend confronted the PR agency, who admitted that none of their current campaigns were working at all. This was a few months ago, just one of countless recent indie releases with high production value that completely and utterly bombed.

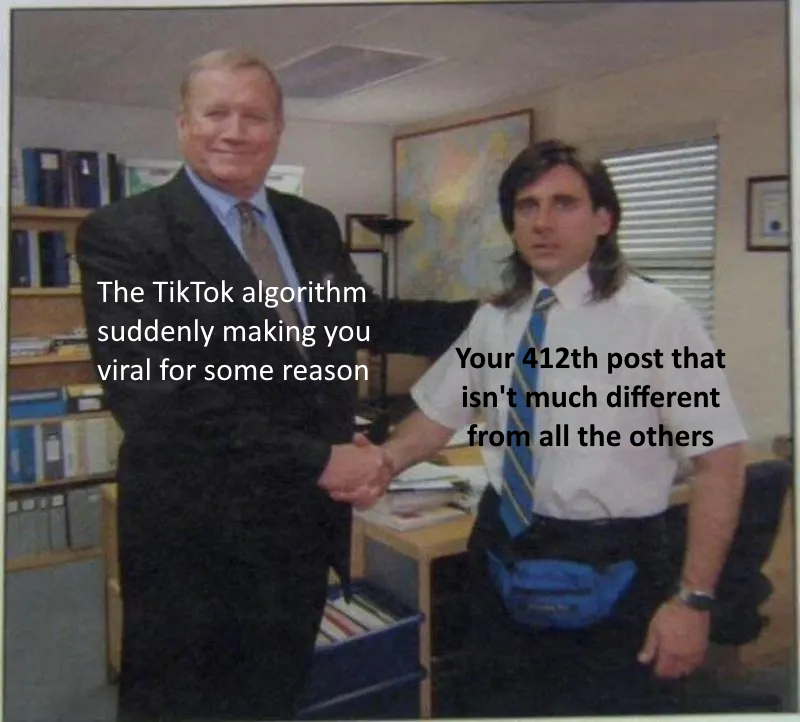

For You can work against you

So why is it so hard nowadays to build an audience to sell your game to? Before we turn to the overcrowded market and the post-COVID bust, I would like to point the finger at social media platforms. They used to be places where you could get the word out to your followers. Unfortunately, followers mean next to nothing nowadays. Chances are that they will never see your content again after they hit that follow button. After TikTok’s success with the For You page, other platforms followed suit, serving up endless content from strangers across the globe that is algorithmically optimized to keep you on their platform for as long as possible.

For example, my girlfriend has over 270.000 TikTok followers. Her least successful videos sit at just 25.000 views (meaning less than 10% of her followers ever got to see them), while the most viewed one has 11.5 million (meaning her followers contributed at most around 2% to its success). You could say that this is great – you may not be able to cultivate fans as easily, but your content has an easier time than ever before reaching new people. While this is true, conversions to wishlists or sales from this type of feed are abysmal in my experience. Very few people will interrupt their scrolling session of infinite dopamine to hop on Steam. If you somehow get them to, algorithms might be quick to punish you and stop serving up your content because they notice that it drives people away from their platform. Some may bookmark the video, but most of them are merely building a separate “to-be-wishlisted” pile of shame on TikTok next to the “to-be-played” one on Steam.

Viral moment

All that being said, For You pages can give your game a considerable boost if you manage to have a viral moment. If the view count is massive enough, even a tiny conversion rate can make major difference. Some developers have been building their games around their viral potential, with the “friend slop” category leading the charge lately. People love watching highlights from these games because they are extremely easy to understand and digest in the span of a few seconds. (And streamers love playing them in large part because they are hoping for a viral moment of their own.)

Unfortunately, Between Horizons is almost the opposite of all that. There are no explosions, silly ragdoll moments, proximity chat, or funny voice filters. It doesn’t have a very clear formula and coherent premise that is quick to get across. On top of that, it’s a wordy, slow-paced singleplayer game where the fun lies in uncovering and understanding a complex story. It builds a relationship with players much in the same way a book does: in a long, quiet session on the couch or at the desk in the privacy of their home. Creating short-form content around it is possible, but very difficult.

Luckily, there is always the route of (perceived) authenticity and relatability that’s doing quite well in this era of parasocial relationships. If your game isn’t exactly a For You page content machine, you can put yourself and the people from your studio in the spotlight. This is not for everyone, and – to me – often comes across as pandering and fake. Some devs go as far as completely making up their own human-interest story. It genuinely pisses me off to see posts hit the front page of Reddit claiming “I quit my job to make this passion project all on my own” when I know the game to be the fifth project of an established 12-person studio. And no, I am not jealous, as we can all play at that game if we want to – I simply dislike lying and liars, and I’ve always wanted Between Horizons to stand on its own rather than generating interest through clickbaity sob stories.

Horrible at live events

On a side note, games like ours also do horribly at live events due to their slow burn approach. Almost nobody takes an hour out of their gamescom schedule to immerse themselves into a story while their friends are waiting to move on, and the neighboring booth blasts loud music in their right ear. At best, people might take a business card and check it out online once they get home. Be very hesitant to drop money on physical events if you’re making games like ours, and consider how much more (and better-suited) coverage it could get you online. Events can worth be your while if you can also score some in-person business meetings and/or if they give you access to a featured Steam sale. If you do end up at an event, and your game does poorly (or very well), the only thing you can safely take away from that is that it’s a very bad (or very good) game for live events. In my experience, this is not at all reflective of its long-term performance on the storefronts.

The industry

It’s convenient to blame the state of the industry, and there is some truth to it. Luckily, in 2021, publishers were still much more willing to sign investment deals, and the German state funding program hadn’t run out of money yet. We managed to secure both for Between Horizons right as these doors started closing slowly.

That being said, the game’s release in 2024 still fell victim to the ensuing bust in multiple ways. In case you’re not aware, the COVID pandemic lead to a growth boom in the industry, as people were stuck at home playing games. Lacuna came out in May of 2021, and there is no doubt in my mind that the pandemic was a major contributor to its success. Throughout the pandemic, publishers and investors were riding the wave and throwing money around to fund a plethora of new projects. Fast forward a few years – the lockdowns are over, people are touching grass again, and the immense volume of games funded during the boom begins flooding the market. One of them is Between Horizons. There is of course no way to peek into an alternate reality where the games traded release windows, but it’s conceivable that our 2021 release would have always outperformed our 2024 release.

Do right and still lose

When you are in an industry, you are always at the mercy of major forces (politics, economics, trends etc.) outside your control. You can do virtually everything right and still lose. This has always been true, but the past few years have made it painfully clear as most (!) of our friends’ studios threw in the towel. These were established companies with multiple successful titles on the market who continued to produce highly polished games with considerable budgets until the very end. In Germany alone, Mimimi Games, Studio Fizbin, Maschinen-Mensch, gentlymad, and countless others – some of which just haven’t publicized it yet – called it quits just over the past two years. The fact that we’re still standing (without having been bought up) almost makes us an outlier.

Go big or go small

I laid out earlier how growing for its own sake was a mistake, and I want to take this thought one step further. Are you ready for my hot take? I believe that mid-sized indie teams are a dying breed.

On one end of the spectrum, teams of 1-5 people on a shoestring budget don’t need much to be sustainable, and even a moderately successful title stands a decent chance of making its money back and then some. Little overhead and shorter development cycles keep things dynamic and efficient. On a small budget, more ideas can be attempted, and they can be bolder. In fact, a good chunk of breakout indie hits in recent memory were created by such teams.

I sometimes believe that the term “niche” is misused by people who refer to a strange or unusual concept that they believe will only reach a few existing hardcore fans. However, there was no “shotgun Russian roulette” fandom waiting patiently for Buckshot Roulette to come out, and the massive audience the game ended up reaching cannot be reasonable described as a niche. Yet, the game is deeply weird and extremely focussed around the “niche” thing that it does. The same goes for Blue Prince, Balatro, Mouthwashing, and many other breakout hits that simply dared to do something that, in my opinion, is only possible with a smaller, determined team on a modest budget. On the other end of the spectrum, there are AA teams upwards of 30 people that can produce polished projects with a wide market appeal and the ability to ship live service content, making the double-digit millions of investment (sometimes) worth it.

Not niche enough

This leaves the middle. Teams that are too big to follow the weird and bold “auteur” ideas, with budgets too high to justify such risks anyway. They often end up with relatively costly, design-by-committee titles that try to appeal to everyone while doing nothing in particular better than any other game. Too boring to stand out, and too small and unpolished to reach a truly big audience, they stand no chance of ever making their bloated budgets back. Many of these mid-sized studios have been closing down or scaling down, and I believe that this trend is here to stay for a long time. To relate this back to Between Horizons, I’m trying to say it might not have been too “niche” – but in fact not “niche” enough.

Part 5: Acceptance

If you’ve made it through all this yapping, you deserve a summary of key takeaways. If you scrolled straight down here: Hi, hello, how does it feel to be a dirty cheater? I’m just kidding, I forgive you.

I’ve grouped these by topic rather than following the train of thought above:

Which game to make (next)

- If you’ve made a successful game and want to stay in its niche, iterate carefully and with purpose. Try new ideas with players as early as possible, especially ones that require expanding the scope and upping the budget.

- Making a sequel is risky because people might, at best, just buy the first game more and never get around to the second.

- From the inception to the execution of your game idea, keep marketability (and maybe viral potential) in mind. Genre, art style, characters, game title, and gameplay need to be a coherent package that immediately communicates the experience in unison.

- Consider mocking up many game ideas quickly and cheaply, get them in front of an audience, and see what sticks.

Production and company pitfalls

These are the most personal and subjective takeaways, specifically for allrounders who could do most or all of it by themselves:

- Be careful about growing your studio. You might burden yourself with overhead, lose ownership and creative control, and bloat the budget just so less experienced people get to do the fun part.

- Give up control of technical aspects at your own peril. Depending on someone with a normal, non-24/7 schedule to constantly fix things for you will slow you down – and once they are gone, good luck creating updates for the game.

- Never create systems, tools, or assets purely based on the assumption that you might need them later.

- The player experience is key, clean code is not. If a quick and hacky solution does the thing you need, it is the best solution. More elaborate systems don’t necessarily break less often, but might take longer to get back into when they do.

Market(ing) perils

- Conventional knowledge doesn’t seem to work anymore, and even big players seem to have no idea what they’re doing when it comes to marketing. Be very wary of giving money to a PR agency or shares to a publisher if they don’t have a stellar track record.

- The For You page has made it impossible to cultivate a recurring audience. Many new people may see your posts, but conversions are horrible. Viral moments are more achievable than ever, but only certain games lend themselves to those. If your game doesn’t, try spotlighting your studio and being relatable.

- If your game does well at events, it won’t necessarily convert to sales – and if it doesn’t, spend your marketing budget elsewhere.

- Mid-sized indie studios shutting down left and right might be more than just the post-COVID bust. The future may belong to big productions on the one end, and small, efficient studios on the other, who operate with budgets low enough to allow for bold ideas that can still reach a surprisingly large audience.

- You can do just about everything right and still fail due to circumstances outside of your control.

A word of encouragement

Most of what I’ve written here might sound horribly grim to you, and I feel the need to put some of it in perspective:

First, this being a post-mortem, I’ve focussed heavily on our mistakes since those teach us the most valuable lessons. We also got a million things right before, during, and after the game’s development. I deeply appreciate and value every single person who worked on Between Horizons internally, externally, and at our publisher, even though I’ve mostly criticized them (and myself) here.

Second, even though many studios have been closing down, and countless people have been laid off, many of them aren’t leaving the industry. Some might be starting something new and incredible right now. In the same period, the market has only continued to grow – and so has the absolute (not relative) number of new releases making good money on Steam. I’ve tried to lay out a few ways to come up with games that might do well, but I’m sure that there are 1000 more waiting to be discovered (by you!).

And finally: We’re just making video games. We didn’t crash a plane or mess up a brain surgery. You live and you learn, or in this case I did the living and hope that both you and I learned something from it. Once we’ve salvaged the past for mistakes to avoid in the future, we can shift our attention forward and think about our next venture that might just turn out better in every way. If it doesn’t, rinse and repeat. After all, you only truly lose the game once you decide to stop playing.