Oscar Salandin, known as Peculiar Pixels, received a major validation for his debut game, BOTSU Ridiculous Robots, by being named the Overall Winner at the Develop Indie Showcase Awards 2024. The English solo developer began his journey right after the Pandemic. He had saved enough money to live comfortably for a few years while pursuing his game development dream. “Inevitably, I’ve gone over time and over budget,” he says. “Finances and time running out are probably the biggest source of stress for me.”

Although he always liked games, Salandin never expected to develop his own. Now, however, he considers it the perfect job for him, even though it can get lonely at times. “I work alone at home, so I will often go all day without saying a word or laughing until my partner gets home, which is very weird for me as I’m quite sociable.” Still, he’s highly motivated to release BOTSU. “I think that anyone making something like this is slightly delusional, thinking that your latest feature is the coolest thing ever,” he admits. “But I think this is needed to keep you going.”

Why did you become a solo developer?

“I never expected I would be working in games at all when I was younger. Even though I was obsessed with games, I didn’t think it was a realistic job at all and I had no idea how it worked. I wanted to design consumer electronics and gadgets so I studied Industrial Design and Technology. By the time I graduated, however, all the gadgets had merged into one black rectangle. I made apps for black rectangles for a bit, then worked in Mixed Reality, which was a much better fit for me, as an emerging interactive medium which involved my 3D design skills.”

“Working in Mixed Reality, I met many ex game devs and artists, who I learned from and was greatly inspired by. Some had worked on AAA games I’d played, released indie games, or previously ran companies in games. Spending time with them demystified the process of making games and the industry for me, and it began to look like something more achievable. Although we weren’t making games, the tech for Mixed Reality was identical to making games, so I picked up a lot of technical ability with Unity, game dev, shaders and more.”

“Many of the projects that I was most proud of were doomed by the pandemic and never saw the light of day, as they were designed as in-person experiences at events and institutions. Lockdown also changed work from an in-person, collaborative, fun experience, to just a thing on my computer screen and something I felt less a part of. By the end of the pandemic, I had gained enough technical ability to feel confident developing a video game. I also came to the realisation that to get something released that people use or enjoy, you don’t need to be a big company, and that being part of a big company might, in fact, make it harder.”

“I had an idea for a multiplayer game I wanted to make (and play). With the technical and financial means now to develop it, and at 30 with no kids, I realised that I would never be better positioned to do this, so it’s now or never. I don’t want to look back in the future and wonder what could have been. So, after much deliberation and many cost modelling spreadsheets, I quit my job to pursue making an indie game, solo. Although I never imagined I’d make a game, it turns out it’s basically the perfect job for me. It’s the combination of all the things I enjoy doing (apart from marketing!): art, design, technology, physics, coding, music, maths, 3D, problem solving, empathy, and fun!”

What are the biggest advantages of working solo?

“For me, the biggest advantages are focus and agility. Since I manage my own time and don’t have to align schedules with colleagues, I can 100% focus on developing the game with no distractions for long stretches during the day. If I’m stuck on a difficult problem and not getting anywhere, I can just stop, go out for a walk or swim, then come back feeling refreshed and continue. It also means I can have a long 2-3 hour lunch break and then work later. This breaks up the day better for me, and I get out in the bright part of the day.”

“Working solo gives me the agility to completely change something without notice, whether it’s the development plan or a core system in the game. Knowing the whole of how something works and all the decisions that were made to make it how it is means I can be quite surgical with changes. It’s very satisfying deleting a huge chunk of your old code. I don’t need to worry about the effects this will have on colleagues’ work, or to pitch, get consensus, defend, or wait for approval, I can just get started and keep the flow going. I do make project plans as a Gantt chart, as working without a plan is disorientating, but I am not tied to it, and it is an evolving thing.”

“Having a holistic view of what you’re making helps with collecting feedback from players, too. It’s easier to understand problems players face and why something is the way it is, so I can have a more informed one-to-one discussion with them about how to improve the game. I really enjoy that in the Discord community. One of the best things about working for yourself is never feeling like you need to be somewhere, or maybe you should have seen some message. Most of the time it’s pretty calm and I don’t need to worry about external pressures.”

And the biggest pitfalls?

“Loneliness. I work alone at home, so I will often go all day without saying a word or laughing until my partner gets home, which is very weird for me as I’m quite sociable. I used to enjoy being in the office so much, seeing what everyone else was working on, helping them solve technical or design problems, helping me with mine and knowing that there was always someone there with the answer to your problem. Even when I was working at home, alone, for most of the pandemic, I would at least laugh with people on calls, but now it’s just 100% focus time. I enjoy focusing on problems, but I miss working with others, the joy of it and having a safety net.”

What’s your creative process?

“Get excited and make things! I’ll often start making before I’ve really thought about the full implications of what I’m making. But if I really thought about that, I probably wouldn’t start! I try to avoid wasting time with high-fidelity mock-ups. I will sometimes sketch out what I’m thinking on paper if necessary, but will always try to use the lowest fidelity needed, then prototype it to find out if it is good/fun/useful.”

“For design problems where the answer isn’t immediately clear, I’ll leave it for a bit, work on something else or take a break, and it’ll be ticking over in the back of my mind when I’m out and about or playing other games. Once I feel that a solution is clear enough, I tend to get a sudden impulse to start making it, so I just follow that urge.”

“Feedback from playtest sessions with friends or players is really important. Especially early-on. From experience, I just assume that any first iteration of something will be obtuse and unintuitive to players, so I’ll try to get past that point as quick as possible by testing with friends, family or whoever is around, then improving it with their feedback. I know I’ve done a good job making something when I see it make sense to people, see them use it without obstructions, enjoy themselves and, ideally, do something I hadn’t expected with it.”

How do you stay motivated through (years of) development?

“I don’t know, really. I’m just pretty addicted to making this game. I think that anyone making something like this is slightly delusional, thinking that your latest feature is the coolest thing ever, but I think this is needed to keep you going. I think if I wasn’t this delusional, then I wouldn’t have made the game, and that would be a shame. The hardest times for motivation are when I am trying to get the game noticed. I find that an uphill battle. I’m not very comfortable with self-promotion, and don’t easily find motivation for things that aren’t contributing directly to the game build.”

“I’m lucky to have friends who are always happy to try out new game builds and give honest feedback for where to improve, as well as saying positive things that keep the motivation up. These days, seeing people’s faces light up and how creative people get with the sandbox is the biggest motivation boost for me. People laugh and smile like I did when I was playing games with friends as a student. Plus, hearing from people who played the demo, really like the game, and want to talk about the details of it is the best. They’ve often got fun ideas for new things to add, which is all I want to do, so that’s great.”

Will you ever work in a team or is it only solo for you?

“I do love working with other people, I miss it a lot, but I also love having absolutely no responsibility. For a while, I thought I would start a larger team to work on BOTSU, and work with others and employ people to work on it. After some time working on it though, I realised that it’s become my baby and a passion project, and I wasn’t able to make it the collaborative project that it should be when you’re working with other people. Plus I had no way of ensuring that it would be a successful game and a long-term job and couldn’t ask others to take the risks I did.”

“There are loads of things I’m not good at, like 3D modelling and texturing (especially colours), PR, marketing, testing, so it would be good to work with someone who is good at those things. If the game can make enough money to employ others, I’d love to do that. I just hope that, after working so long on this solo, I won’t be a massive micro-manager nightmare colleague! I know how much of a difference it makes to have a good manager and I’d hate to be a bad one.”

How did you get the idea for BOTSU?

“When I was a university student, I played a very early version of Gang Beasts, and it just felt like something completely new and different. It had none of the visual polish or online modes that it does now, but they made the movement so creative and unique, it was just so fun and fascinating. We’d plug 8 controllers into my PC and have such a laugh playing all night. I was intrigued by the physics-based animation but I had no idea how it worked at the time. I’ve always enjoyed games with more direct, open-ended controls, and sandboxes like Just Cause 2, Crysis, Rocket-League and Halo, but none of them had done this to the actual character. I sought out other active ragdoll games like Sumotori Dreams and Human Fall Flat, but none quite had the agility I wanted.”

“I was inspired to make the ultimate sandbox game, all physics-driven, even the characters, but without being sluggish, slow or drunk like other active ragdoll characters. Most active ragdoll games make things easier for themselves by using stylised character proportions. Long arms and short legs mean that you can reach objects on the floor without bending down, and the legs don’t really need to walk properly and can’t get caught on each other. The difficulties of controlling a ragdoll character mean that these characters often appear slow and drunk, which is pretty funny to watch, and a big selling point for these games. They can’t even run, because it’s hard to animate legs with physics.”

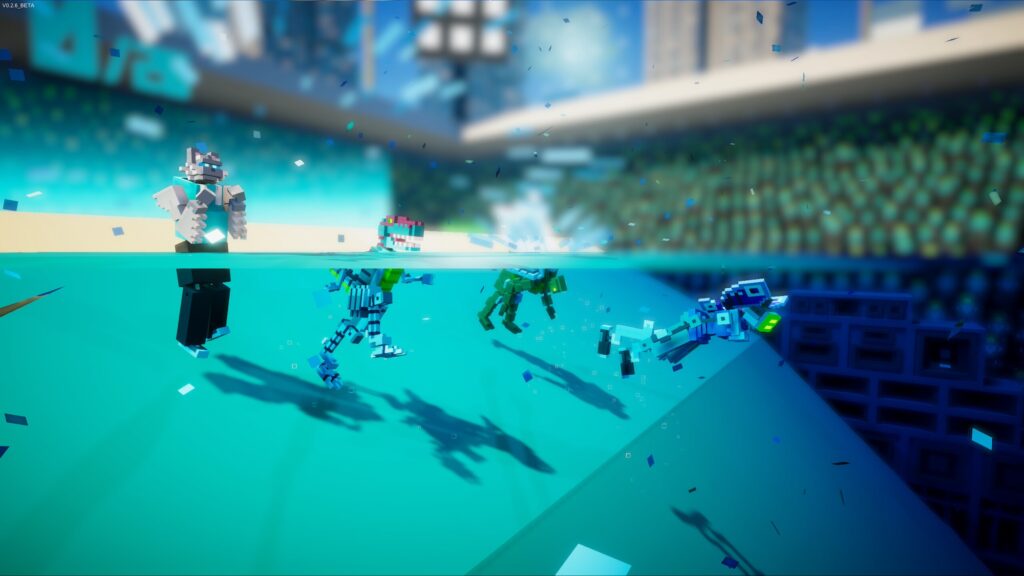

“I wanted to control a character that had proper agility and didn’t have these limitations. I was much less interested in the drunk aspect than I was in how it opened up the possibilities for gameplay. My idea was an athletic, realistically proportioned, superhero or ninja character, like Spiderman. One that could run, jump, swing, climb, fly, flip and fight in a fluid way. One that could do anything, if you were able to pull it off. The ragdoll characters in BOTSU certainly aren’t perfect, and still have a slightly drunk element to their movements, but it was a big step from the games that inspired me to make it, and opened up a whole range of new, faster-paced gameplay possibilities that these games did not have.”

“With this character controller, you can move yourself, other players and objects, so I made game modes built around controlling those. These are essentially the building blocks of all sports, so I based the game around sandbox “sports”. I’ve never particularly enjoyed watching sports, but always enjoyed playing them. I played a lot of Rocket League, and liked what it took from sports, in terms of rounds, replays, teams and upbeat atmosphere, so tried to bring that energy to this game, moving it further away from the other active ragdoll games.

How did you finance this project?

“I’ve been financing BOTSU out of my own savings. The combination of a well-paid job and not enjoying spending money meant that I saved money without a real plan for what to spend it on. The pandemic helped a lot with saving, too, going a couple of years without beers, gig tickets or holidays. With the tools to make games being largely free for small projects, and not needing any specialist equipment, it’s just my living costs that need to be covered.”

“I made financial plans with spreadsheets and graphs (so many graphs), trying to estimate how much time and money I would spend on the project before I should get a ‘real’ job again. Inevitably, I’ve gone over time and over budget. I drew a line in the savings where I would stop, but I’ve had to redraw that line a few times now. I’m not really able to do that again. Everything takes longer than you think, and the cost of living has risen a lot since I started. Finances and time running out are probably the biggest source of stress for me.”

The toll on your mental health can be quite high for solo developers. How do you deal with that?

“I’m quite lucky with that, as mental health struggles were not new to me going into this job. Growing up around people with mental illness, and having had my own periods of depression and anxiety, I was raised to see this as an illness, not a personal weakness. I think this made it a lot easier to separate it from myself, discuss it with family and friends and seek treatment when needed. Having watched ‘Indie Game: The Movie’ years ago, plus knowing that I’m prone to some of these issues, I went into solo dev knowing it would come up, so I always try to keep an eye on it.”

“For me, it’s a lot like a cold or flu. There are situations that can put me more or less at risk of it, things I can do at home to remedy it, but if it sticks around too long or gets more severe, there are doctors, medicines and therapies to help treat it. For general prevention, I get out every day to do some exercise, get some fresh air, and think about something other than games. I try to plan and look ahead to avoid surprises, and I have two lovely cats, who inject some serendipity into an otherwise uneventful workday. I’m lucky to have an incredibly supportive partner who puts up with me venting my frustrations and problems to her regularly. It’s helpful to get these things off my chest and put into perspective by someone else so they’re not running in circles in my head. Writing things down helps too.”

“When I’m feeling particularly stressed, anxious or down, getting out of the flat and changing my environment helps a lot. When I come back, I’m normally feeling calmer, or excited again. One of the benefits of being solo is that you can just go do this whenever you need. Taking time off is important and I don’t do it enough. Especially being solo, any time you’re not working on the game, it doesn’t move forwards. This weighs on me a lot, as the clock is ticking to run out of time and money.”

“Another really important one for me is avoiding clickbait game dev content and news. I try to avoid social media in general, but I do need it to connect with players. There are so many headlines and thumbnails designed to make you feel like the industry is moving so fast with AI, Unreal 5, or how Unity is becoming irrelevant and you are getting left behind. It’s mostly rubbish. It’s very important to play other games to appreciate, learn, and be inspired by them, but it’s not helpful to see a very survivor-biased view of others’ successes. The less I’m comparing myself and my game to others’ success, the better.”

“These days, I try to replace watching videos about games or devs with actually playing games, or watching videos about other stuff, like engineering, maths, science, music or comedy. It’s made a huge difference. These stresses and lows are outweighed by the joy of seeing people enjoy playing the game, especially in groups of totally different ages, or even strangers having fun playing together and laughing. Now that BOTSU is close to release, I see it stand up on its own, with people to play for hours and it all goes smoothly, all the complications become irrelevant and I feel very proud to say that it’s my game.”