Belgian solo developer Thomas Waterzooi didn’t start his journey with a master plan, just a growing dissatisfaction with the AAA game industry and a desire to create something more meaningful. “I didn’t want to continue working on these AAA titles where violence was often the main mechanic,” he recalls of his time freelancing on the Hitman series. When that job came to an end, in 2016, Waterzooi found himself at a crossroads. A manifesto about making games for ‘a new audience’ helped him finally take the leap. “Then I knew I needed to pick a topic that my mom and non-gaming friends would also find interesting: modern art!”

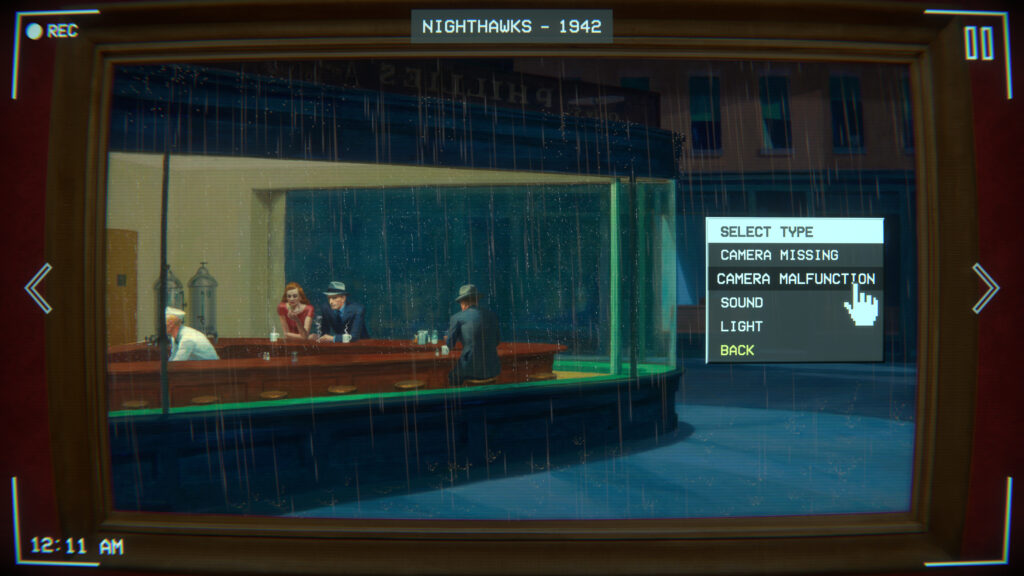

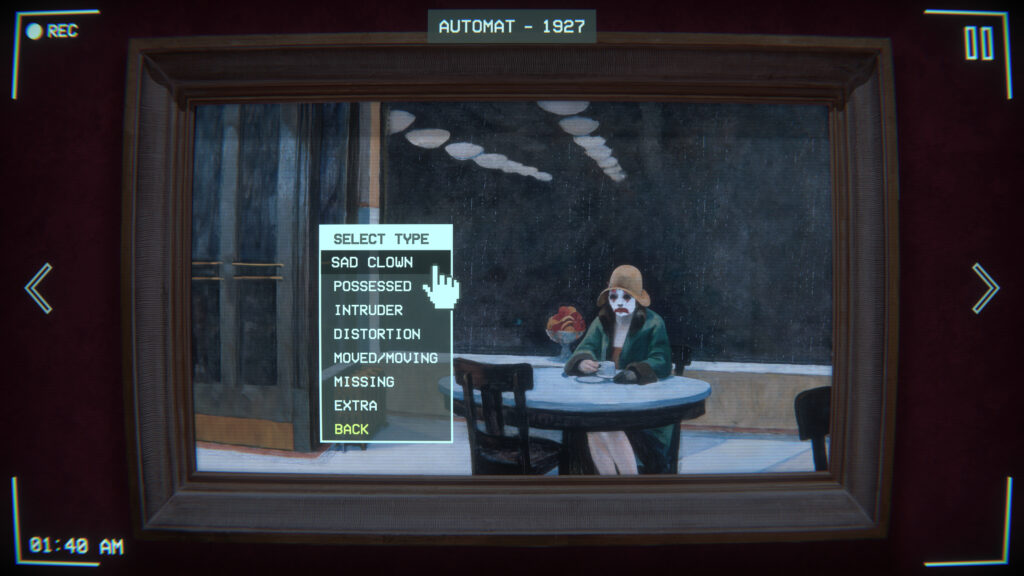

That leap led to Please, Touch The Artwork, a meditative puzzler that struck a chord with players and platform curators alike. But solo development has its trade-offs. “The biggest advantage is immediately the biggest struggle: you don’t have to answer to anybody, so you have full creative freedom.” An advantage that quickly becomes a pressure cooker without teammates to validate decisions or share the load. Making and releasing games is hard work and Waterzooi finds the experience quite intense at moments. “I have to accept a six month depression period after each release. Accepting it as part of the process makes it easier to cope with.” Still, Waterzooi remains committed to personal, art-inspired experiences. After Please, Touch The Artwork 1 & 2, he just announced his next game Please, Watch The Artwork at the Day of the Devs stream.

Why did you become a solo developer?

“After being let go from working freelance for IO-Interactive on the Hitman series in 2016 when they lost their publisher Square Enix, and had to fire half the company. I had been thinking about making my own games for a long time but I was afraid to take the step. Also, I didn’t really know what games to make, only that I didn’t want to continue working on these AAA titles where violence was often the main mechanic. No judgement, it just didn’t interest me anymore.”

“It’s only after a year and a half of searching that I stumbled onto Manifesto Rejecta, a game-design manifest written by Pietro Righi Riva, on how to make games for what he calls ‘a new audience’. Adults, with adult interests, who don’t see games as a medium that addresses these interests. Then I knew I needed to pick a topic that my mom and non-gaming friends would also find interesting: modern art!”

What are the biggest advantages of working solo?

“The biggest advantage is immediately the biggest struggle: you don’t have to answer to anybody, so you have full creative freedom. That also means you have to make all decisions yourself, without anybody telling you whether they are good or bad. For me it’s also: being able to pick the hours that I work, which is mainly at night.”

And the biggest pitfalls?

“Working in your bubble without asking feedback from players and/or colleagues, and potentially making decisions that don’t make the game better. Adding features to your game because you think it’s not interesting enough, mainly because you know it by heart and for you it has become boring. Getting burned out faster because you have to carry all the load and you might not know when to stop.”

What’s your creative process?

“For the first game I imposed a process on myself called ‘visual-first’ design. The idea is that you start from a visual theme instead of from a mechanic. I would choose a painting I like, try to generate it procedurally (so I could create an infinite amount of variations of this painting), and only then add the gameplay and story-elements. This generally worked but was quite stressful at times when I had some form of random generation but couldn’t come up with a cool mechanic and had to start over with another painting.”

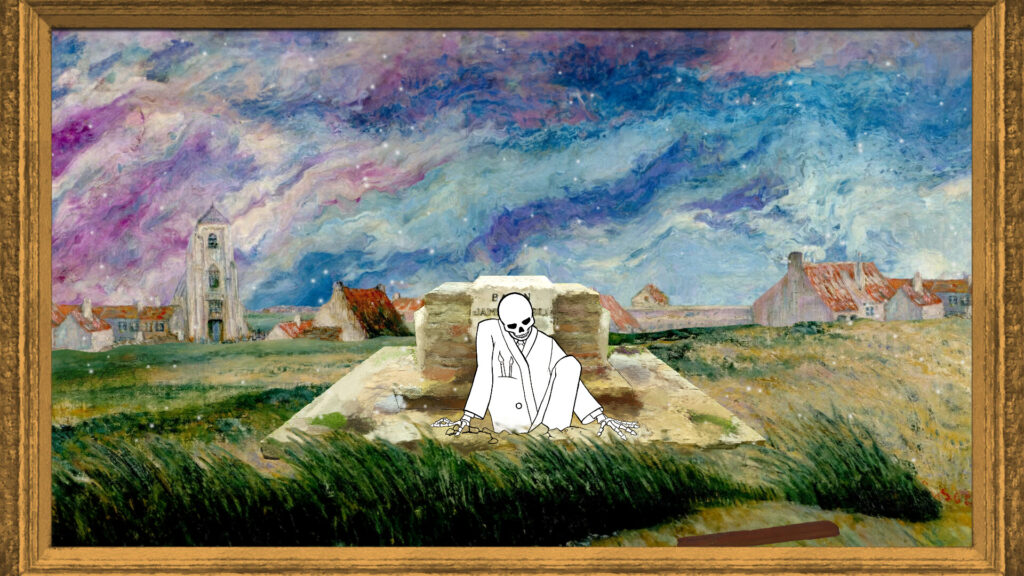

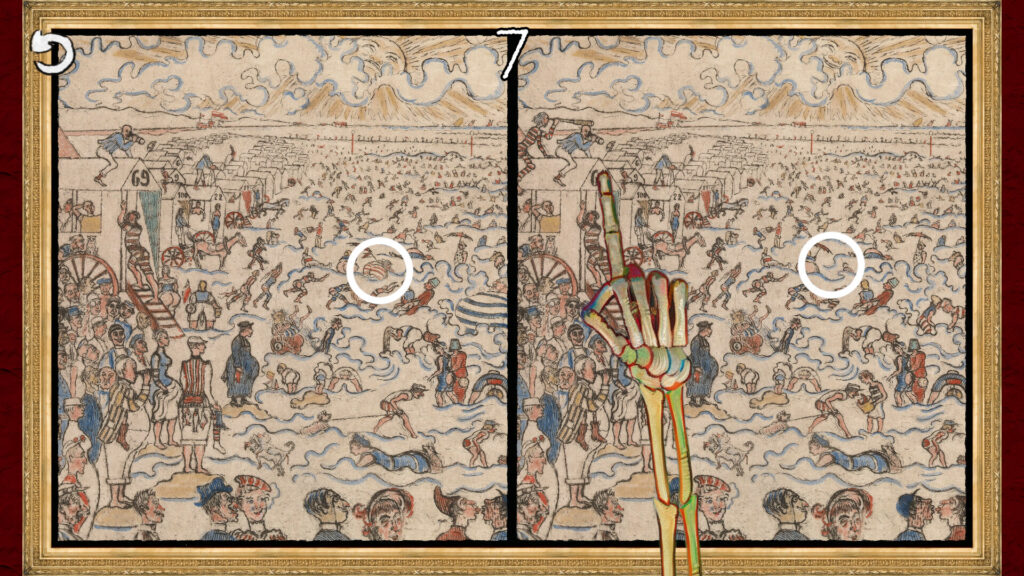

“For the second game I decided to use the original paintings (from James Ensor), but collaged them together to form new paintings and cut-out characters to animate them. Admittedly, I played around with AI and trained a model with his paintings but afterwards I thought: what’s the point? The work is in the public domain and it just feels cooler to know these are existing paintings. The process was still similar: I looked at the paintings and thought about what mechanic could fit. It was actually my partner who said: ‘this looks a bit like ‘Where’s Waldo’, why don’t you just make it a hidden-object game?’ – and so I did.”

How do you stay motivated through (years of) development?

“I actually concluded from the first game that I wanted to have shorter production periods. Let’s say one year max. To avoid overscoping, project fatigue and having smaller budgetary risks. While the first game took me around 5 years on and off, the second game was made in 9 months, so I know it’s possible!”

“But the real answer to this question is: playtesting. Nothing gives you as much motivation to continue working as some good constructive feedback at a cool event. In Brussels we do monthly meet-ups in a bar under the name ‘Brotaru’, where we playtest games and have free drinks, all very informal.”

Will you ever work in a team again or is it only solo for you?

“I’m a bit of a control-freak. I did work with a sound-designer/composer for both the games, and had an illustrator/animator helping out with characters in the second game. But they were all freelancers. I would love to try a project with 2 people. That’s literally doubling your capacity! Two years of work would become one year. It has to be someone who’s better than me in certain aspects. The problem is, these people usually have a job, or are working on their own projects. And I don’t want to work on someone else’s idea, asking them to compromise on certain stuff because I don’t agree, ending up with something neither of us really likes. I like what Sokpop was doing for their 1 game-a-month project: each team-member alternates between becoming the lead for a project. I imagine this becomes trickier for bigger projects though.”

How did you get the idea for Please Touch The Artwork?

“One of the guidelines of manifesto Rejecta is to get sources outside of existing game-culture, and for me that became real-world art. In 2018 I was reading a book called ‘What Are You Looking At? 150 years of Modern Art in a nutshell’ by Will Gompertz. It’s an anecdotal and informative book which sketches the chronology of the origins of modern art, from the impressionists to the present. You go on a journey and read about where these artists lived and worked, who their friends were and what drove them to make their art.”

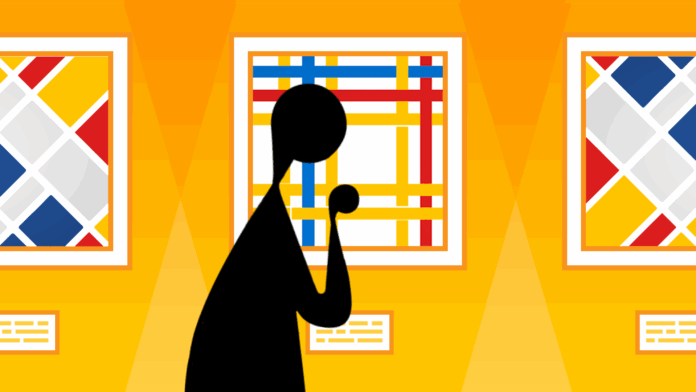

“During a night of light insomnia I wanted to try writing a Mondrian-painting generator which randomly generated paintings based on Mondrian’s famous Compositions in Red, Blue & Yellow. I thought it’d be interesting if touching a painting revealed a hidden world behind the static canvas, one never meant to be seen (hence all the ‘Please, Don’t Touch The Artwork’ signs in museums). I added a little puzzle mechanic and ‘Please, Touch The Artwork’ was born. Success is relative but it certainly resonated with some people and platforms like Google Play and Apple App Store. I think this is due to the universality of the topic of ‘art’. So the manifest was right!”

What’s the biggest lesson you learned from your two solo games?

I made ‘Please, Touch The Artwork’ in a very ‘naive’ and artistic way, not thinking about genre or audience. The biggest lesson learned was that people have genre-related expectations. When you fail to meet those expectations you get negative reviews. Or even worse: when people don’t get what your game is about, they won’t buy it. In hindsight this is super obvious: when I browse Netflix I also immediately need to know what a show is about and if I’m in the mood to watch it.”

Were you ever worried that your first solo game might not be a big hit right away?

“Yes of course! Luckily a large part of the project was subsidized so I didn’t have any large personal investments to recuperate. While porting the game to Nintendo Switch, I had to start thinking about a new project. Cozy/wholesome games became very popular during the development of my first game and I felt this was the closest ‘genre’ I could relate to. However, while working on a new cozy project (still unannounced) I was approached by the Department of Youth & Culture to make a sequel to my first game but with a Flemish artist. This game was distributed for free as a ‘gift’ of culture from the Flemish government but it triggered a spike in the sales of my first game.”

The toll on your mental health can be quite high for solo devs. How do you deal with that?

“It’s true. Releasing a game is always stressful, even more so when you’re alone. In case of a failure, you have only yourself to blame. But of course it’s not that straightforward and we should not measure success just in terms of sales. There’s also the fact you made the game you wanted to make. It might just be too niche for the current market, or didn’t manage to reach its target audience. Unfortunately, it’s not easy to convince yourself of this.

I’ve also concluded (from exact empirical measurements after releasing two games which is a large enough sample, haha) that you have to accept a six month depression period after each release. Accepting it as part of the process makes it easier to cope with. ‘This too shall pass’. The only thing you can do is take some vacation and start working on the next game.”

Please, Touch The Artwork 1 & 2 are out on Steam and Nintendo Switch. Please, Watch The Artwork will be out later this year. Wishlist here.